- Infographics:

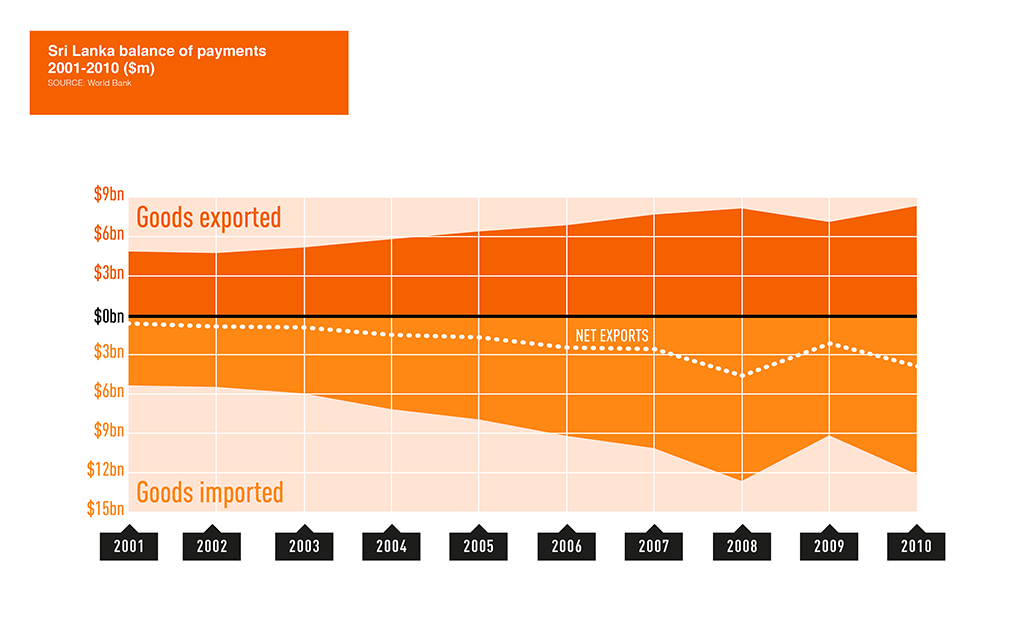

- Sri Lanka BoP

- |

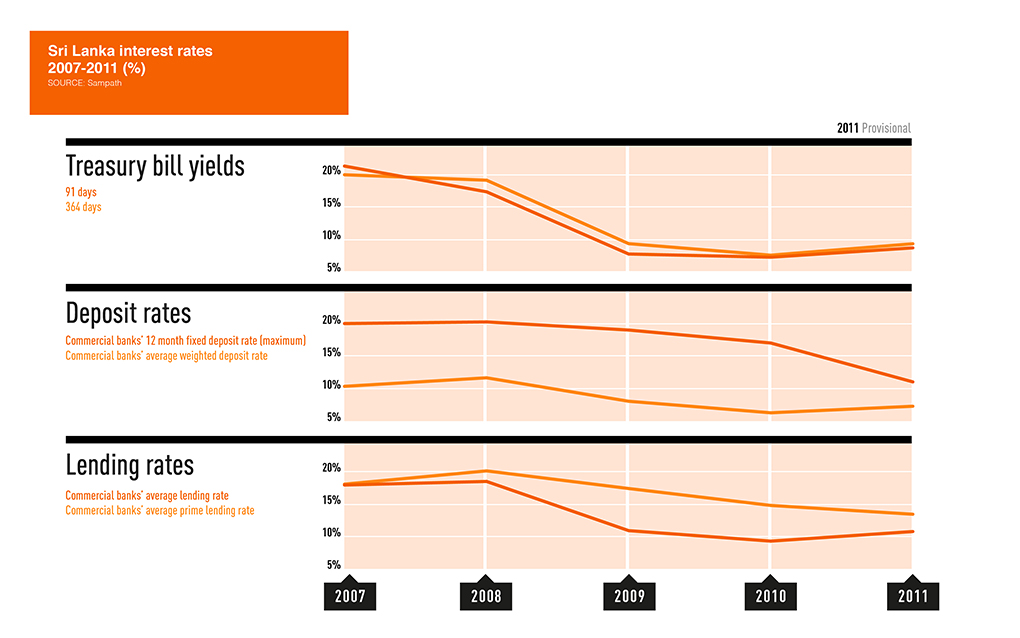

- Sri Lanka interest rates

- |

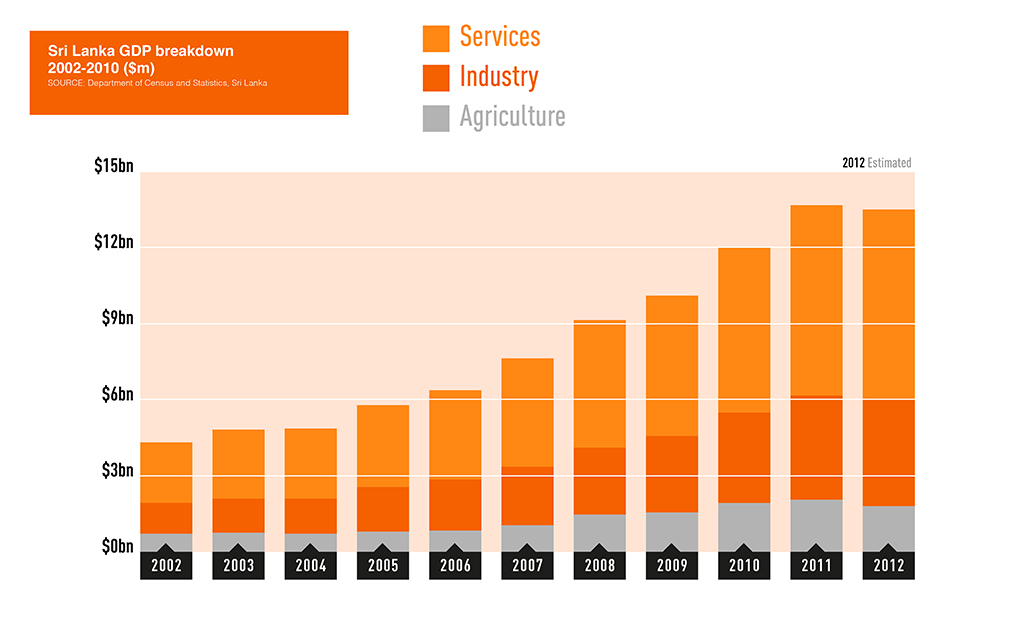

- GDP breakdown

- |

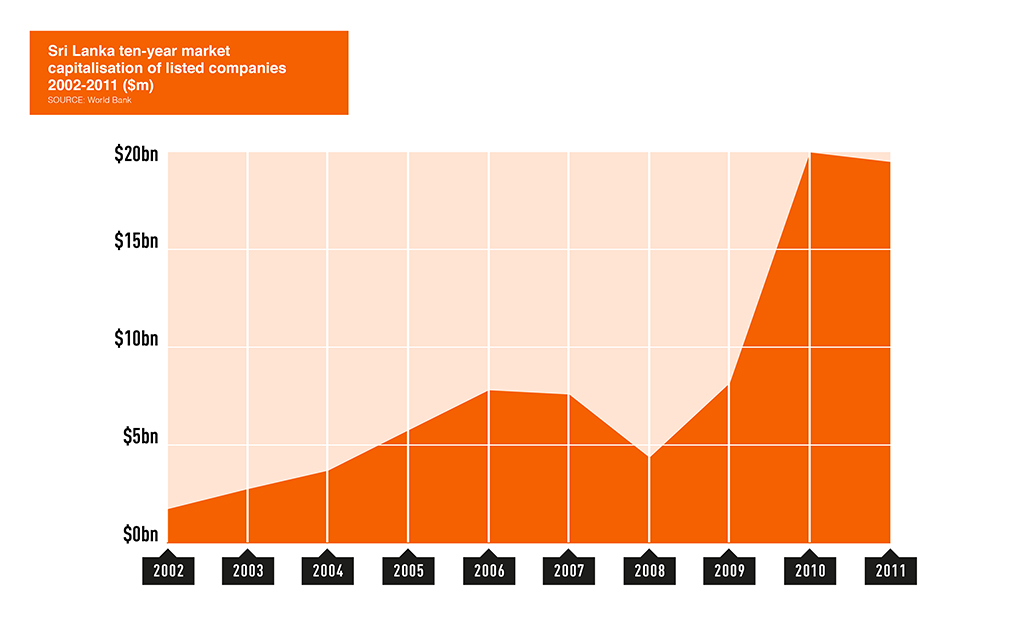

- Market capitalisation

- |

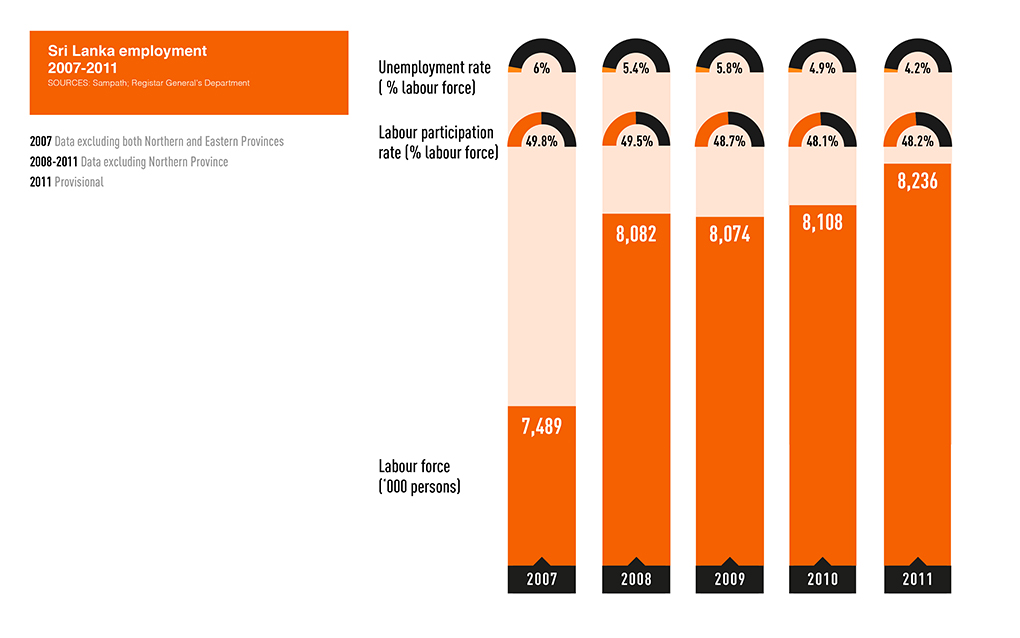

- Employment

- |

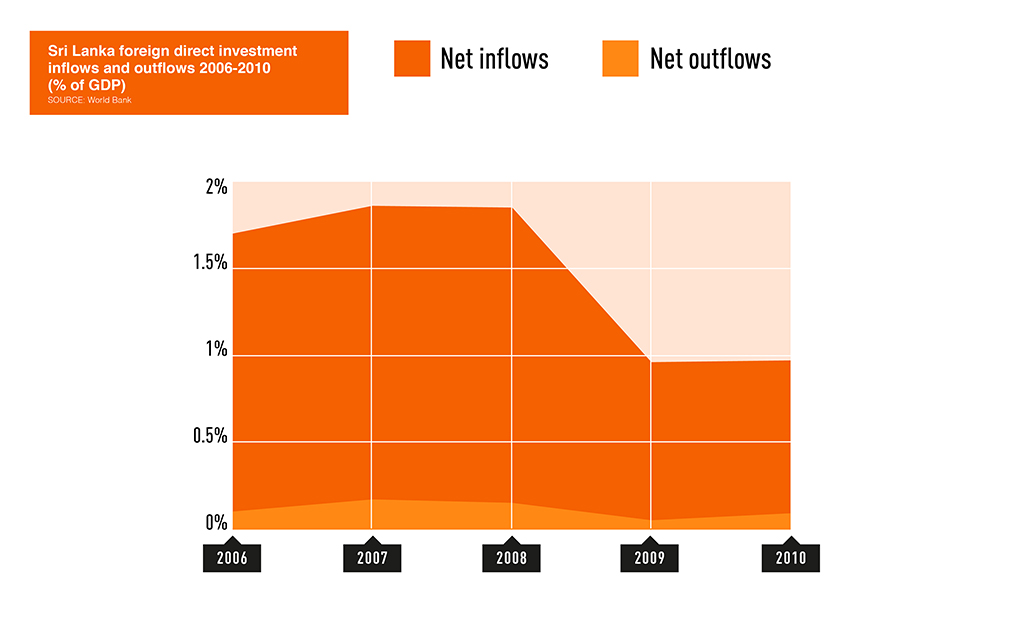

- FDI

Following a civil war in 2009 and a per capita income of below $2,000 in 2008, development in Sri Lanka has since been recovering. The nation has been taking major steps to create new investment opportunities and maintain a stable banking system to further aid its economy.

If per capita income growth is one yardstick to measure Sri Lanka’s development, it has self-evidently passed that particular test, having evolved from a low-income country with a per capita income below $2,000 as recently as 2008, to a lower-middle income one, with income forecast to be $3,000 at the end of 2012. Underpinning development in Sri Lanka has been educational advancement, skills development and the promotion of the country as an international service centre for shipping and aviation – helped in no small part by an improving investment environment after investors’ perceptions changed following the civil war, which finished in May 2009. Once hostilities ceased – the economy quickly rebounded, with real GDP growth of eight percent in 2010 after just 3.5 percent in 2009.

If per capita income growth is one yardstick to measure development in Sri Lanka, then the country has self-evidently passed that particular test. Since 2008, Sri Lanka has evolved from a low-income country with a per capita income of below $2,000, to a lower-middle income one, with the average income forecast to be at $3,000 at the end of 2012.

Development in Sri Lanka has been underpinned by educational advancement, skills development and the promotion of the country as an international service centre for shipping and aviation. This has been helped in no small part by an improving investment environment following the civil war, which finished in May 2009. Once hostilities ceased, the economy quickly rebounded, with real GDP growth of 8 percent in 2010 after just 3.5 percent in 2009. Now the challenge is to sustain economic growth and encourage investment in Sri Lanka. In this endeavour, the banking system undoubtedly plays a major role.

Sri Lanka has a concentrated banking sector. According to ratings agency Fitch, the six largest local Lincensed Commercial Banks (LCBs) identified as systematically important are as follows: Bank of Ceylon (BOC), People’s Bank (PB), Commercial Bank of Ceylon (CB), Hatton National Bank (HNB), Sampath Bank Plc (SAMB) and Seylan Bank (SEYB). As of the end of 2010, these banks collectively accounted for 64 percent of the sector’s assets, 74 percent of loans and 68 percent of deposits.

Just over half of all bank loans in Sri Lanka are dispensed to corporates, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Foreign ownership, on the other hand, has remained relatively low at 12 percent, although the largest foreign bank branch (HSBC Sri Lanka) accounted for five percent of sector assets at the end of the same period. Meanwhile, foreign-currency-denominated lending has similarly remained limited, accounting for about 16 percent of sector loans at the end of 2010. Such lending is principally funded by foreign-currency deposits and generally limited to companies deriving revenues in foreign currency or to the Board of Investment of Sri Lanka-approved companies.

In a recent special report on Sri Lanka’s banking sector, Fitch noted a steady outlook regarding the long-term ratings of most banks in the country. In a separate report, Sampath Bank, was rated top of its industry peer group.

With real GDP growth likely to drive strong credit demand, inflation remains a residual threat to the pace of development in Sri Lanka over the medium term. In the meantime, the World Bank is set to more than double its lending to $500m in order to help spur investment, sustain economic expansion and promote further development in Sri Lanka as the authorities continue to restructure the economy to help cement its middle-income status.

The regulatory and supervisory framework for banks operating in Sri Lanka, such as Sampath Bank, is set out in the Banking Act, Monetary Law Act and the Exchange Control Act. In terms of asset base and the scale of services provided, LCBs are the single most important category of financial institution within Sri Lanka’s financial system. As of September 2011, LCBs, including Sampath Bank, held a market share of 46 percent of the entire financial system’s assets, according to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL).

Licensed Specialised Banks (LSBs) on the other hand, have been relatively less important to development in Sri Lanka and its financial system, accounting for around eight percent of the entire system’s assets.

Breaking the numbers down further, fee/commission income and foreign exchange income accounted for 43 percent and 12 percent respectively of the non-interest income of the five largest local LCBs in 2010 (38 percent and 20 percent in 2009). Non-interest income for some banks in 2009 and 2010 was boosted by mark-to-market and capital gains on equities and government securities. As of the end of 2010 there were 31 licensed banks including 22 LCBs and nine LSBs – half of the LCBs having foreign bank branches, four of which were branches of Indian banks, according to Fitch. The number of LCBs increased to 24 in 2011 with the granting of licences to Amana Bank Ltd and Axis Bank of India.

Customer reach – in terms of banking sector development in Sri Lanka – is still largely carried out through the traditional “bricks and mortar” model – i.e. in branches, given use of alternate delivery channels remains limited. The geographical dispersion of branches in recent years has been skewed towards the western Province – the civil war having undermined, to some extent, further development in Sri Lanka. Development in Sri Lanka and the growth of its financial system more generally has also been aided by business generated from the pawning of products such as gold, enabling local operators, such as Sampath Bank, to increase their lending through pawning advances.

In 2010 alone, according to Fitch, banking sector-pawning advances grew by 40 percent and accounted for 14 percent of sector loans that year. Sampath Bank, like others, has regarded this business as a low-credit risk, zero-risk weight and attractive in terms of yields. Pawning advances generally carry a maturity of one year or less.

Unsurprisingly, development in Sri Lanka has accelerated in recent years, helped in part by an improving political climate. Also, Sri Lanka’s reputation for hospitality is well documented. Driven by public investment in the tourism subsector and the rising importance of the financial subsector, the services sector is forecast to grow eight percent next year. Private consumption and investment, meanwhile, is forecast to grow 8.8 percent and 8.1 percent respectively in 2012. Home-grown financial entities, such as Sampath Bank, remain intrinsically linked to development in Sri Lanka by helping to improve the nation’s infrastructure.

For the foreign investor considering setting up a company in Sri Lanka – while using the services of Sampath Bank or others – approval is required from the Board of Investment (BOI) – an autonomous agency and the primary government body responsible for foreign investment. Under Section 17 of the BOI law concessions are granted to companies satisfying certain eligibility criteria.

With the government looking to encourage further development in Sri Lanka, investors are offered preferential tax rates, constitutional guarantees on investment agreements, exemptions from exchange controls and 100 percent repatriation of profits and capital. The scale of tax incentives given to investors is determined in part by the sector in which the money is being invested. Tax holidays and duty exemptions are also available.

Under Section 16 of the BOI law, the Sri Lankan government permits up to 100 percent foreign participation in many sectors of the economy. Investment in certain restricted sectors is subject to screening and approval is given on a case-by-case basis if the foreign investment exceeds 40 percent. Key to continued development in Sri Lanka remains a continuation of post-civil war political stability.

Despite the global financial crisis, earlier regulatory initiatives have ensured that Sri Lanka’s banking and finance sectors have remained resilient. Indeed, development in Sri Lanka has continued apace without the banking failures witnessed elsewhere, post Lehman Bros – the notable exception being in December 2008 when Seylan Bank, a competitor of Sampath Bank, faced liquidity problems after Golden Key Credit Card Company failed to repay customers who’d placed funds in the firm as deposits for credit cards.

The collapse of Golden Key – a subsidiary of the Ceylinco Consolidated Group and major shareholder of Seylan Bank – and the resulting liquidity crisis prompted the CBSL’s monetary board to bring Seylan Bank under the control of state owned Bank of Ceylon via Section 30(1) of the Monetary Law Act No.58 of 1949, thereby allowing Ceylinco to exit.

One significant initiative instituted in May 2008 and aimed at furthering development in Sri Lanka has been the requirement that all banks have a minimum exposure to the agricultural sector equivalent to 10 percent of their loan portfolios, effective at the end of 2009. Banks failing to comply are compelled to contribute any shortfall to a refinancing fund operated by the CBSL, to be drawn on by other banks.

More generally, licensed banks like Sampath Bank, are required to comply with the requirements of the 1988 Banking Act in areas such as capital adequacy, liquidity, related party exposure, classification of loans and advances, income recognition, provisioning, risk management and so on – which will further aid development in Sri Lanka more indirectly.

Unsurprisingly, compliance with these regulations is monitored on an on-going basis and any corrective action can be initiated if needed. Regulations have similarly been framed with the global Basel III Framework (governing capital adequacy) in mind.

Another major development in Sri Lanka was the introduction of a mandatory deposit insurance scheme in 2010, aimed at ensuring continued depositor and investor confidence, as well as the financial system in general. Under the scheme, depositors are compensated up to a maximum of R.200,000 per depositor. A Deposit Insurance Fund, operated by the Monetary Board of the CBSL, is separate from the Central Bank and its liability is limited to the extent of the Fund’s balance.

To fund the scheme, premiums (as a proportion of eligible deposits) are required to be paid by member institutions on a monthly/quarterly basis. This comes on top of the R.1.1bn originally provided to the scheme, in the form of initial capital, by the CBSL. Figures from the CBSL show the deposit insurance fund amounted to R.4.7bn by the end of 2011. This financial safety net mechanism is supplemented by access to the CBSL as ‘lender of last resort’.

The CBSL also decided at the time to reduce the general provision on performing loans and credit facilities in the special mention category from the then 1 percent to 0.5 percent – effective December 31 2011 – at a rate of 0.1 percent per quarter, starting from the quarter ending December 31 2010.

Its argument at the time was that with the domestic economy growing rapidly in a stable environment and the country’s banks improving their asset quality over the previous few months, the need for provisions against future losses had substantially abated. The loan-loss provision requirement was originally introduced back in 2006 to provide a cushion against any meltdown of the global economy.

In addition to banks such as Sampath Bank, all licensed finance companies (LFCs) and specialised leasing companies (SLCs) are closely monitored and regulated by the Central Bank. LFCs and SLCs are subject to on-site examinations at least once every two years with weekly, monthly and quarterly reports required through a web-based data reporting system. Aside from the regular supervisory procedures, spot examinations are conducted when the Central Bank identifies an issue.

The recent institution of the Finance Business Act, No. 42 of 2011, provides for enhanced supervisory and regulatory powers on LFCs and powers to curb unauthorised finance business. All LFCs are required to list with the Colombo Stock Exchange in order to increase the transparency of financial and corporate governance.

The capital base of the banking sector has increased nearly two fold since 2007 with the introduction of the Basel III Framework enhancing the minimum capital requirement for local banks.

To further aid development in Sri Lanka – at least when it comes to buttressing the banking sector – authorities have also tightened up the classification rules governing NPLs (non-performing loans). In particular, all credit facilities extended to a borrower have to be regarded as non-performing when one or more facilities have been classified as ‘non-performing’ and in aggregate exceed 30 percent of the total credit facilities extended to the borrower.

In its mission statement, Sampath Bank describes the creation of a learning culture promoting individual and organisational development as well as innovation and value for customers – based on the bedrock of “uncompromising ethical and professional standards of behaviour.” Aravinda Perera, recently installed as managing director of Sampath Bank, told Sri Lanka Business Report earlier this year that for banks, including Sampath Bank, living with lower margins is becoming a way of life, especially when compared to a few years ago. The key issue now is adapting to the new reality by ensuring operations are more cost effective. Just as development in Sri Lanka accelerated, Perera said that Sampath Bank underwent a rapid expansion of its branch network – doubling its size in a matter of years. Not all Sampath Bank branches are making money however and a more short-term objective is to get them to do so.

The net interest margin has dropped significantly not only for Sampath Bank, but the industry as a whole. Credit demand remains good but deposits aren’t coming in as quickly as the bank would want. And that poses a challenge because it is customers who decide where to save their money. The reality is that Sampath Bank and its competitors will need to look at alternative ways of generating money as the market evolves, rather than simply being reliant on interest-income alone. The use of fee-based commission structures is one way forward.

Perera added that although Sampath Bank is looking at so-called ‘brick and cement’ branches, the development of mobile banking opens up further opportunities for a technological innovative bank such as itself.

Sampath Bank also sees mileage in the north and east of the country – a non-existent branch network there five years ago now sees 30 branches, which will help to promote further development in Sri Lanka. Agriculture is another area for enhanced development within Sri Lanka that Sampath Bank is looking at, given expectations of higher credit demand from the north and east of the country. However, manufacturing and services are also likely to see further growth as development in Sri Lanka continues apace.

Perera says Sampath Bank will be there to leverage wherever growth occurs – the stated objective being for the bank to increase its overall market share. Asset growth for Sampath Bank this year is forecast at 30 percent, although 25-30 percent would still be seen as a great accomplishment.

Sampath Bank was recognised in the World Finance 2012 Banking Awards, as the Best Banking Group, Sri Lanka.

In March 2012, Sampath Bank Group reported on its 2011 full year pre-tax profits which totalled Rs. 5,983m up 24.8 percent on 2010 – Sampath Bank itself posted a 23.9 percent gain of Rs. 5,579m.

Addressing investors in Colombo, Sampath Bank executive director and Group CFO, Ranjith Samaranayake, said that while the latest numbers provided further confirmation of the foundations already laid for long-term profit growth and enhanced stakeholder returns, key challenges for the bank remained; including a fall in net interest margin from five percent in 2010 to 4.13 percent in 2011, along with mark-to-market losses on its trading portfolio coming in at Rs.189.6m. in 2011, against a net-gain of Rs.333m. in 2010.

That said, the prognosis for Sampath Bank, and in many ways development within Sri Lanka in general, has changed little since Fitch re-affirmed its positive outlook for the bank in September 2011, citing strong asset quality, profitability and a comfortable equity buffer against future loan losses. The rating also implied the bank’s ongoing contribution to development in Sri Lanka. It added that the outlook also factored in the bank’s rapid growth from 2010 – “driven by continuous improvements in credit metrics, supported by ongoing structural changes in the bank, as well as a growing franchise and market share in terms of deposits, loans and assets.”

Gross NPLs (non-performing loans) at Sampath Bank fell by 30.7 percent on an absolute basis in 2010, and a further 3.8 percent in H1 2011, supported by enhanced recovery initiatives and tighter underwriting standards as well as an improved economy the agency further noted.

Against this backdrop the bank’s gross NPL ratio at 3.2 percent (2010: 4.0 percent), was still substantially better than that of its peers – in part due to a substantial pawn-broking (gold-backed loans) portfolio (22 percent of advances at H1:2011) with very few NPLs. Specific loan-loss coverage stood at 79 percent in the case of Sampath Bank – this compared to an industry peer average of just 49 percent. By the end of 2011 it had marginally fallen to 77.3 percent, compared to an industry average of 45 percent.

The agency also believe that while incremental capital generation at Sampath Bank is supported by high return on assets (ROA), the bank’s capital base may require further strengthening to enable it to maintain capitalisation levels commensurate with its rating category – if the current growth momentum is sustained.

Profitability at Sampath Bank has been rising since 2007, generally supported by improving net-interest margins, lower provisioning costs, and a largely stable cost-structure, despite the expansion of its branch network. Expectations are that ROA will continue to improve as the bank’s newly set-up branches continue to generate deposits and assets.

Branch expansion was the core strategy of boosting the presence of Sampath Bank across the country as it took advantage of the post-civil war political landscape. In 2011, Sampath Bank opened 35 new branches nationwide, bringing its total network up to 206.

From a ratings action standpoint, Fitch says any upgrade for Sampath Bank will depend on its ability to: “meet or surpass core capitalisation relative to its local and regional peers over the medium-term, particularly in view of its continued high loan growth, while maintaining strong asset quality and robust core ROA.”

Conversely, the outlook for Sampath Bank may be revised to stable if “growth momentum results in a further dilution of its core capitalisation to levels more in line with its lower-rated peers.”